In a largely democratic world, freedom is an inherent right of every man – the right to decide upon his life and pursue his goals freely. The question is, however, to what extent one’s life can be considered controllable and not driven by fate? How much freedom does one actually have over their life? These are the kinds of “dilemmas” that haunted humanity from the very beginning – perhaps prompting the search for a higher power and fostering the belief that there’s some sort of a greater purpose in simply “not knowing”.

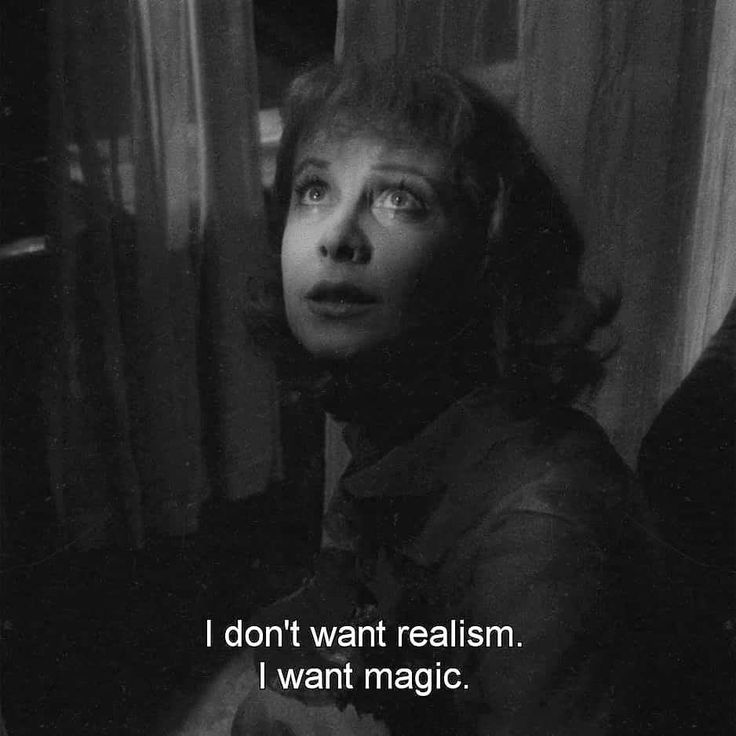

As one might imagine, freedom is an intricate concept that, despite occupying a significant place at the core of society, to this day remains widely misunderstood and often oversimplified. It’s this very theme of the “liberty of choice” that the movie directed by Elia Kazan, based on John Steinbeck’s novel – “East of Eden” – revolves around. The story is set in Salinas Valley, California, in the early 20th Century – right before the first World War. The main character, Cal, starring James Dean, is a troubled son of a ranch owner, Mr Trask, who’s struggling to meet his father’s expectations, living in the shadow of his brother, Aron – who as Mr. Trask claims, he has “always understood”. Cal’s introduced to the audience as the troublesome kid who acts impulsively, out of reason, and leads a solitary lifestyle – he’s hiding away from people, sneaking around, jumping on trees, and train wagons – which visibly concerns those around him. His father yells at him for sneaking out of the house, his brother’s gilfriend, Abra, calls Cal a “prowler”, and frequently mentions that she’s afraid of him. He can’t help but feel unseen and misunderstood by his relatives – viewing himself as the “rotten one” in his family, the black sheep among its kin. He channels his frustration by acting mindlessly, setting out onto the vicious path of self-destruction. For instance, when asked by his father about him sneaking into the freezer and throwing out all the ice intended for Mr. Trask’s “refrigerating business”, Cal simply answers that he wanted to see it “go down the chute.” “Cal, listen to me.” – announces his father – “You can make of yourself anything you want. It’s up to you. A man has a choice. That’s where he’s different from an animal.”

In the spur of the moment, Cal implores Mr Trask for the truth about his mother, only to uncover that she had fled to the east shortly after his birth. Without telling anyone, he begins the search for his mother, hoping to find answers and reach the awaited closure, accepting it as the reason why he’s different. Once he manages to find her, he discovers the real motive that led her to run away from Salinas. She admits that she was unhappy in her marriage, feeling caged, and eventually, chose freedom – a life of independence, not dictated by anyone else. Finally finding purpose, motivated by the “liberty of choice”, Cal resolves to reconcile with his father and support him in his refrigerating business, which, as Mr. Trask believes, will prove to be “revolutionary”. “It’s not about making profit, Cal.” – he declares, driven by the pure desire to commit something impactful for society, something lasting, of immeasurable value. Despite his efforts, the business quickly collapses and our main character, eager to continue his newfound journey, finds himself working to repay Mr. Trask the lost funds. He starts his own business from scratch, and when he finally manages to earn the money back, his father declines the grand gesture, explaining that he wished Cal’d given him something of genuine value – something, such as Aron’s and Abra’s engagement, which happened to be announced on the same day. The following turn of events reaches a tragic culmination when Cal loses his temper and suddenly reveals to his brother the secret behind their mother’s “death”. Aron finds himself unable to cope with truth and rapidly spirals into mental distress, adopting a new vulgar behavior – he’s engaging in street fights and decides to enlist in the military for the impending war. Taken aback by Aron’s “out-of-character behavior,” Mr. Trask suffers a heart attack, leaving him tied up to his bed like a vegetable, unable to speak or move. Ironically, both his “revolutionary” business and Aron’s future crumbled, unable to withstand the test of time – the years of striving toward a greater goal turning into dust. Similarly, Cal, who rose to achieve his goal through a deliberate choice, discovered himself powerless in the face of his father’s insensitivity – his money couldn’t buy love, it couldnt liberate him from the persistant feeling of being the family’s dissapointment.

The story of the Trasks in “East of Eden” sets a powerful example of the profound ways in which the freedom of choice can affect one’s life. In the spirit of the American Dream of the 1900s, the characters in the film express a strong belief that complete independence is the key to a happy and successful existence. Cal’s father maintains the belief that an individual’s destiny relies on their choices – there’s an unlimited array of opportunities out there, each one with the power to change one’s life. Conversely, Cal’s mother believes that even if a choice results in loss, it remains worthwhile as long as it is an independent decision. Aron, Cal’s brother, makes a choice that compromises all his prior life decisions, including the good education and the engagement with Abra. Lastly, Cal strives to make a meaningful choice and become a greater person in his father’s eyes. Yet, he fails miserably, as Mr. Trask fails to see between the lines – he’s unable to detect the value in his son’s hard work, and discern the deeper meaning.

While all these characters consciously make free decisions, they seem completely obsolete towards the so-called “natural ways of life”. The fabric of existence is uncertain, shaped by the intricate interplay of our individual choices. In a way, we all shape each other’s decisions. Despite perceiving them as independent, it is often these “freely made” choices that impose the most significant constraints on our personal freedom. Of course, it’s important to have a choice – it prompts us to account for different possible outcomes, and acknowledge our full potential. Yet, sometimes the abundance of choices leads us to make poor decisions, as we’re driven by the thrill of unrestricted freedom and opportunity. A man does have a choice. Yet, he should use it wisely.